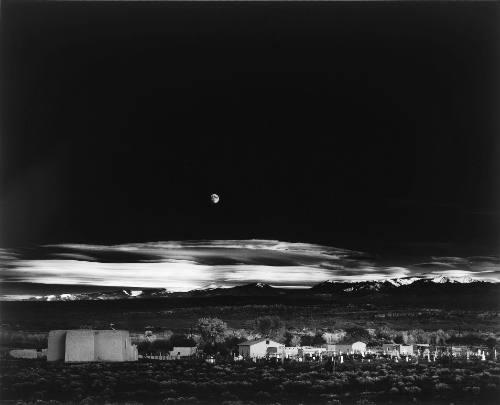

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico

Sheet: 15 1/2 x 19 1/4 in. (39.4 x 48.9 cm)

When he was fourteen years old, Ansel Adams took his Brownie box camera to the Yosemite Valley and began his lifelong interest in landscape photography. While documenting specific locations, he also hoped to reveal, in the tradition of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, the spirituality within nature. He started working for the Sierra Club in 1920, becoming its official photographer by 1928. Trained as a musician, Adams supported himself playing concerts and teaching until 1930, when he turned his attention fulltime to photography.

While working as a photomuralist for the Department of the Interior in 1941, Adams shot Moonrise Hernandez, New Mexico as part of an assignment to create a series of portraits of different regions of the country. Although signs of humanity are evident in the pueblo church, cemetery, and scattered buildings in the foreground, they are dwarfed by nature; over half of the image is the night sky with the moon hanging slightly off center. Adams developed what he termed the zone system to control the tonal range from dark to light with a high degree of precision. The photograph reads as alternating bands of dark and light, beginning at the bottom with the stretch of desert shrubs in shadow, followed by the highlighted buildings, and on up through the landscape into the sky. The pure white ribbon of clouds and the moon, thrown into stark relief by the inky sky, vie for the viewer’s attention with the highlighted crosses and tombstones. Reinforced by the sharp focus, the image conveys the photographer’s awe before the sublimity of nature—his rumination on humanity’s insignificance before natural forces.

Throughout his career, Adams devoted himself to promoting nature and photography. His breathtaking photographs of remote areas of national parks increased awareness of conservation and preservation efforts. Through exhibitions, publications, and related efforts—including cofounding both the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in 1940 and the magazine Aperture in 1952—he brought greater critical recognition to the art of photography, while increasing its popularity.