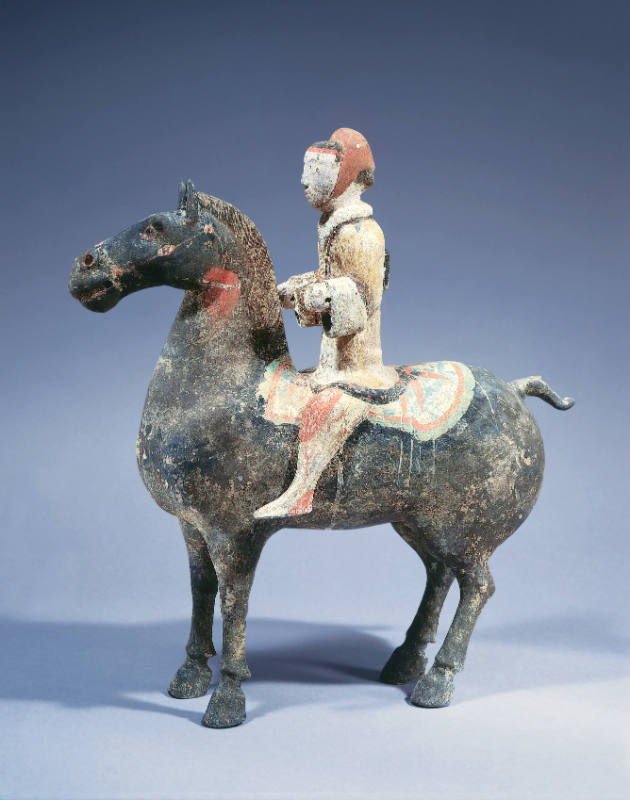

Horse and Rider

One of ancient China’s most prosperous periods was the Han dynasty. During this time literature and the arts flourished. Confucianism was reestablished as the official ideology and these renewed beliefs encouraged the use of small models in burials, replacing the earlier practice of human and animal sacrifice. The Chinese tradition of elaborate entombment continued, and replicas of material possessions, animals, and people were placed in tombs to accompany and serve the deceased in the afterlife. Usually formed from clay or wood, these representative objects, called ming ch’i, often depicted servants, musicians, farmworkers, jugglers, elaborate houses, watchtowers, watchdogs, barns, granaries, pigpens, fowl, and horses.

Tian ma, or celestial horses, came to symbolize prestige, power, and wealth during the Han dynasty. Described as superlative in every way, this new breed of horse was brought from Fergana (a present-day province of Russian Turkestan) to China by Han emperor Wu Di (141 – 87 B.C.E.) to enable his armies to fight invading equestrian soldiers. Horse and equestrian sculptures became essential elements in the furnishing of important tombs. Modeled in clay, this horse with a neatly hogged mane, a docked tail, and erect ears is typically Ferganan in style–fat, strong, and powerfully built with slender limbs. Ready for battle, the rider sits erect in the saddle, wearing a headdress, a short padded robe, and on his back a small quiver, in which small arrows might have been placed originally. His garments are elaborately painted in cinnabar, black, and white. The black body of the horse is contrasted with the bright green, vermilion, blue, and white of the saddle blanket and trappings. At one time miniature reins made of rope, cloth, or metal were probably looped through the holes in the horse’s mouth and the rider’s hands. This polychrome equestrian figure signifies the Han dynasty fascination with horses, as well as the importance these animals served in the military and the afterlife.